Imagine if your studies extended beyond the classroom and into communities where innovation becomes a practical tool for meaningful change. That’s the essence of the Frugal Innovation for Sustainable Futures (FI4SF) minor — a unique collaboration between Leiden University, Delft University of Technology, and Erasmus University Rotterdam. Over the course of three months, students explore the intersections of development, technology, and entrepreneurship, gaining insights into the power of frugal innovation. Equipped with this knowledge, they take on the challenge of applying their skills in resource constraint settings, abroad or in The Netherlands.

One such challenge led students to Makueni County, Kenya, where they worked on a greywater reuse project in Mbuvo-Nzau, a rural community facing severe water scarcity. Their mission? To develop a locally viable, cost-effective filtration system that could turn used dishwater into a reusable resource—enhancing both household resilience and sustainable livelihoods.

The Challenge: Water Scarcity and Livelihoods Under Pressure

Makueni County is semi-arid, with erratic rainfall and limited access to clean water. Residents, mostly small-scale farmers, rely heavily on seasonal rain and spend hours each day fetching water. Addressing this issue required more than just engineering skills—it called for cultural awareness, adaptability, and community engagement.

From the start, the team took an immersive approach, conducting interviews with local farmers, market vendors, NGOs, and even government officials to identify key livelihood constraints. Water access emerged as the most pressing issue, directly impacting agriculture, household chores, and overall economic stability.

The Frugal Innovation Approach: Doing More with Less

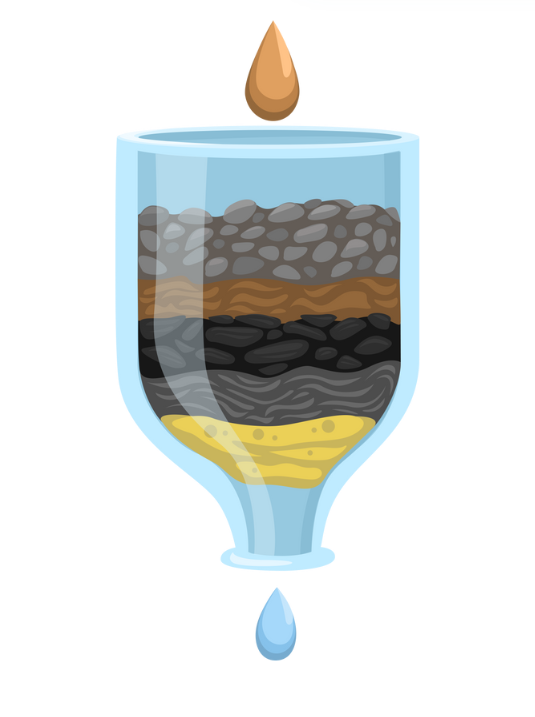

Frugal innovation means designing affordable, simple to use, and resource-efficient solutions tailored to local constraints. With limited materials, transport challenges, and no access to high-tech lab facilities, the team had to think creatively. Their solution? A multi-layered filtration system made from locally available materials, such as sand, gravel, and crushed charcoal.

How the Greywater Filter Works:

- Pre-filtering: Food debris is removed using a simple sieve.

- Primary filtration: Water passes through gravel and cotton layers to catch larger particles.

- Main filtration: Sand and crushed charcoal absorb contaminants and improve water clarity.

- Plant-based purification: The system incorporates coriander plants, known for their ability to remove nitrogen-based pollutants.

- Final step: Boiling ensures the water is safe for household use.

By using readily available materials, the team kept costs low—an essential factor, as community members emphasized affordability during interviews.

Testing and Realities in the Field

While the concept was promising, implementation in real-life conditions came with challenges

- Material constraints – The nearest town, Kitui, had only a small selection of construction materials, requiring adaptable designs.

- Water quality issues – Initial tests showed high turbidity and soap residue, prompting a search for better filtration materials, such as biochar instead of crushed charcoal.

- Cultural adaptation – Community members welcomed the idea but had concerns about practicality, such as the size of the input reservoir and whether coriander plants added enough value to justify the cost.

To validate their design, the team traveled to the Kenya Water Institute in Nairobi for a full chemical and bacteriological analysis of their filtered water. While some parameters met drinking water standards, others, such as organic compounds, still required improvement.

Despite this setback, the students gained valuable insights into both frugal innovation and the realities of working in resource-constrained environments:

1. Community engagement is key – Local buy-in determines the success of any innovation.

2. Frugality isn’t just about cost—it’s about adaptability – Transport, availability, and usability matter as much as affordability.

3. Iterative design is essential – More testing and refinement were needed, and starting trials earlier could have improved outcomes.

4. Interdisciplinary collaboration is crucial – Working with SEKU (South Eastern Kenya University) students and local experts was invaluable in navigating cultural and logistical challenges.

A Lasting Impact: Beyond the Classroom

The experience was transformative—not just for the community, but for the students themselves. Living in Mbuvo-Nzau meant adapting to a different pace of life, where office meetings happened under a tree and translation difficulties shaped how research was conducted. As one student put it:

We realized just how frugal our intervention had to be. Many community members said, ‘We would like to, but we cannot afford it.’ However, people were incredibly open to learning new things—if given the tools and guidance.

For the students, the biggest takeaway wasn’t just technical innovation, but the power of co-creation and deep community engagement. The project may not have ended with a perfect solution, but it laid the groundwork for future innovation—proving that frugal innovation isn’t just about products, but about people, partnerships, and progress.

Watch the students' journey unfold in their video presentation here:

More videos of the Minor 2024-2025